By Anthony Karabanow, M.D.

By Anthony Karabanow, M.D.

Disease specific discussions (HIV, TB, malaria etc) often dominate the attention and funding of the global health community.

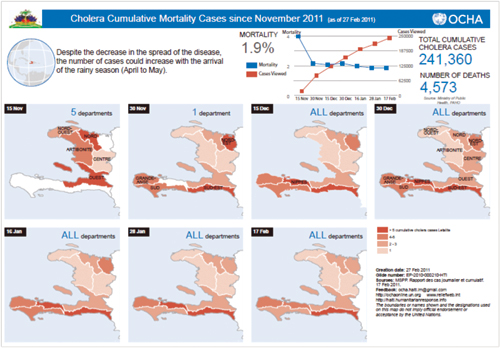

However, the pivotal role of sanitation was made clear by the recent cholera epidemic in Haiti. While the responsible strain of cholera was imported from South East Asia, the devastation imposed by this disease was wholly the result of profound inadequacies of Haitian sanitation and medical infrastructure.

The most recent UN data are quite staggering. The Haitian epidemic began in the center of the country – in the Artibonite Valley. It then spread in a centripetal fashion.

Clinical Presentation of Cholera

Clinical Presentation of Cholera

Cholera is a diarrheal disease which can rapidly dehydrate infected persons due to tremendous fluid losses in stool. The cholera cots – cots with a hole cut in the bottom – are a well known testament to this. The infected individual lies on the cot weakened by the disease. Stool is collected is collected in a bucket under the hole cut in the cot.

Vast amounts of replacement fluid (both intravenous and oral) are provided in order to keep ahead of the fluid losses. The balance between diarrhea and fluids determines whether the patient will live or die. Thus, cholera is a labor intensive disease for the medical care giver.

Buckets must be emptied, oral fluids must be constantly encouraged and IV bags frequently changed. Diarrhea and vomit are both highly contagious. Thus there must be scrupulous attention to hygiene and waste disposal.

Hôpital Sacré Coeur Responds to the Cholera Crisis

Hôpital Sacré Coeur was able to prepare itself for the inevitable spread of the disease into the surrounding areas. The tent hospital which had served as the trauma center for the earthquake victims was converted into a cholera treatment center.

As a closed off area, cholera patients could be isolated from the general hospital patient population. Cholera cots were fashioned by cutting holes in available cots. Thanks to a well-established supply chain, large quantities of intravenous fluids, oral rehydration packs, buckets and cleaning supplies were delivered. Care delivery and waste disposal protocols were collaboratively developed. Dr. Prèvil held regular meeting with the hospital staff to ensure a high level of education and preparation. The site was visited by a team of cholera experts from Bangladesh and further training sessions held. As always, volunteers willingly came to support the Haitian staff.

As a closed off area, cholera patients could be isolated from the general hospital patient population. Cholera cots were fashioned by cutting holes in available cots. Thanks to a well-established supply chain, large quantities of intravenous fluids, oral rehydration packs, buckets and cleaning supplies were delivered. Care delivery and waste disposal protocols were collaboratively developed. Dr. Prèvil held regular meeting with the hospital staff to ensure a high level of education and preparation. The site was visited by a team of cholera experts from Bangladesh and further training sessions held. As always, volunteers willingly came to support the Haitian staff.

The Cholera Patient Faces Severe Challenges

In the vast majority of patients, cholera is a mild (or asymptomatic) illness. In contrast to dysentery, the cholera patient is afebrile and there is no blood in the diarrhea. Patients arriving at a cholera treatment center are first assessed for degree of dehydration using clinical criteria.

| No Dehydration |

Some Dehydration |

Severe Dehydration |

|

| Condition | Well, alert | Restless, irritable | Lethargic or unconscious |

| Eyes | Normal | Sunken | Sunken |

| Thirst | Drinks normally, not thirsty |

Thirsty, drinks eagerly |

Drinks poorly or not able |

| Skin Pinch | Goes back quickly | Goes back slowly | Goes back very slowly |

Patients with no dehydration are discharged home with instructions to maintain adequate oral hydration with oral rehydration solution (ORS). ORS is made by mixing a package of sodium, potassium and sugar with sterile water. Patients with moderate dehydration are kept for observation. These patients are aggressively treated with oral rehydration solution. Follow up observation determines the need for further hospitalization.

Patients with no dehydration are discharged home with instructions to maintain adequate oral hydration with oral rehydration solution (ORS). ORS is made by mixing a package of sodium, potassium and sugar with sterile water. Patients with moderate dehydration are kept for observation. These patients are aggressively treated with oral rehydration solution. Follow up observation determines the need for further hospitalization.

Amount of ORS to be given in 1st 4 hours

| Age* | <4mths | 4-11mths | 12-23mths | 2-4yrs | 5-15yrs | 15yrs+ |

| kg | <5kg | 5-7.9kg | 8-10.9kg | 11-15.9kg | 16-29.9kg | 30kg+ |

| ml | 200-400 | 400-600 | 600-800 | 800-1200 | 1200-2200 | 2200-4000 |

*Age should be used only if weight is not known

Only those with severe dehydration are treated with intravenous hydration. The ideal fluid for cholera patients is lactated ringer’s (with normal saline as a second choice) as this best matches the fluid losses in diarrheal stool. Intravenous fluid therapy is very aggressive initially to address the profound fluid losses in such patients.

Only those with severe dehydration are treated with intravenous hydration. The ideal fluid for cholera patients is lactated ringer’s (with normal saline as a second choice) as this best matches the fluid losses in diarrheal stool. Intravenous fluid therapy is very aggressive initially to address the profound fluid losses in such patients.

| Age | First give 30ml/kg in | Then give 70 ml/kg in |

| Infants | 1 hour* | 5 hours |

| Older Children | 30 mins* | 2.5 hours |

*repeat once if pulses are weak or not detectable.

These patients are kept under close observation in the hospital to determine their intravenous fluid needs. These patients are discharged when they are no longer dehydrated and can maintain hydration orally.

Unlike fluid resuscitation, antibiotic therapy is not essential in the treatment of cholera. Antibiotics are given to those with severe symptoms to reduce the volume of diarrhea and to reduce the bacterial counts (i.e. infectivity) of the stool. Doxycycline is often given in a single 300 mg dose to adults.

Pregnant women and children can be treated with a short course of erythromycin. In children, supplementary oral zinc is also provided.

Pregnant women and children can be treated with a short course of erythromycin. In children, supplementary oral zinc is also provided.

Hôpital Sacré Coeur Meets Fears with Education and Outreach

Efforts were also made by the HSC staff to address the considerable fears and misunderstandings regarding cholera in the Milot community. Unrest did occur over the influx of cholera patients from the Cap Haitien area and the disposal of cholera waste from the hospital. HSC staff repeatedly met with community members to explain the nature of the disease, the activities of the cholera center and the appropriate preventative measures.

Cholera can be a frightening disease to providers, patients and community members alike. Common misconceptions typically concern the nature of disease transmission and the best treatment strategies. Cholera is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. This means that cholera transmission only occurs through the consumption of contaminated food and water. Thus, community education focuses on appropriate hand hygiene, thorough cooking of food, the consumption of clean water and appropriate sanitation practices. Cholera treatment should focus on oral rehydration using ORS and not on antibiotic and intravenous fluid therapy unless absolutely necessary. It is very rare for care providers to become ill with cholera if common sense hygiene practices are followed. Antibiotic prophylaxis for care providers is thus unnecessary.

Cholera can be a frightening disease to providers, patients and community members alike. Common misconceptions typically concern the nature of disease transmission and the best treatment strategies. Cholera is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. This means that cholera transmission only occurs through the consumption of contaminated food and water. Thus, community education focuses on appropriate hand hygiene, thorough cooking of food, the consumption of clean water and appropriate sanitation practices. Cholera treatment should focus on oral rehydration using ORS and not on antibiotic and intravenous fluid therapy unless absolutely necessary. It is very rare for care providers to become ill with cholera if common sense hygiene practices are followed. Antibiotic prophylaxis for care providers is thus unnecessary.

Dr. Mark Walsh ended up at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer (in the heart of the cholera epidemic) when unrest in Milot prevented his arrival at HSC. During that time, he encountered many patients who presented very late to seek medical care. These individuals were profoundly dehydrated and near death.

Unfortunately, their severe dehydration makes the placement of intravenous lines very difficult.

Unfortunately, their severe dehydration makes the placement of intravenous lines very difficult.

When these lines were placed, aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation resulted in remarkable recovery. The challenge was clearly to improve the delivery of intravenous fluids. This challenge was best met under such circumstances with the use of intraosseous needles. These special needles are drilled through bone to access the bone marrow in patients for whom regular intravenous access is impossible. Dr. Walsh subsequently convinced the founder of the EZ-IO company to provide these life saving tools to HSC and other sites in Haiti.

The Future of Cholera in Haiti

Given Haiti’s profound deficiencies in sanitation, cholera will likely become an endemic disease. The answer will never be intravenous fluids or antibiotics but rather investment in creating a system for the appropriate disposal of human waste and the provision of safe drinking water. Attention to such mundane issues will define Haiti’s rise from its current third world status.

Anthony Karabanow, M.D. is a hospital based internist who resides in Albuquerque, NM. He attended medical school at the University of Connecticut Health Center and did his residency at the University of Wisconsin Hospital. He subsequently trained in tropical medicine at Johns Hopkins. His interests include medical education and global health. He is currently chairman of the CRUDEM medical education committee.

Anthony Karabanow, M.D. is a hospital based internist who resides in Albuquerque, NM. He attended medical school at the University of Connecticut Health Center and did his residency at the University of Wisconsin Hospital. He subsequently trained in tropical medicine at Johns Hopkins. His interests include medical education and global health. He is currently chairman of the CRUDEM medical education committee.