By Albert F. Fleury, Jr., M.D. and Joan Frawley Desmond

By Albert F. Fleury, Jr., M.D. and Joan Frawley Desmond

During my first trip to Hôpital Sacré Coeur, an intern asked for my help treating a young woman who had been injured in a motorbike accident, and suffered from multiple cuts and scrapes on her face, hands and arms. The intern was particularly concerned about a nasty laceration involving the lower eyelid and cheek.

A plastic surgeon with 30 years experience in the field, I was used to treating such injuries in a well equipped modern emergency room where everything that I needed was readily at hand. In Milot, the patient was in a tiny room with barely enough space for two people to treat her.

After evaluating the injuries, we use a local anesthetic to numb the area of the injury so that we can clean it properly, examine the extent of the injury, and plan the repair. The local anesthetic generally used in these situations, has two components. First there is the anesthetic itself–lidocaine, which numbs the area to enable cleaning and repair without pain. The second component is epinephrine. That component reduces the bleeding so the plastic surgeon can see all of the delicate structures.

I asked for ½ % lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The intern, Dr. St. Fleur, found it after considerable searching, and returned with a small bottle, and set it on the table next to the patient. But as we prepared the rest of the instruments, she moved her foot and knocked the bottle of anesthetic on the floor where it broke. I said to Dr. St. Fleur, “That’s okay, just grab another one.” He replied, “There is no more that is the last one in the hospital.”

At that moment, the simple lesson in treating a laceration became a lesson in preparing your own lidocaine with epinephrine in the proper concentration from individual vials of each. This procedure was followed by difficulties finding the appropriate suture material and making do with well worn or “worn out” instruments. As Dr. St. Fleur received a lesson in caring for traumatic injuries of the face, I received my first lessons of what to expect in Haiti.

At that moment, the simple lesson in treating a laceration became a lesson in preparing your own lidocaine with epinephrine in the proper concentration from individual vials of each. This procedure was followed by difficulties finding the appropriate suture material and making do with well worn or “worn out” instruments. As Dr. St. Fleur received a lesson in caring for traumatic injuries of the face, I received my first lessons of what to expect in Haiti.

What did I learn from that first lesson?

Everything takes longer than you think it will. You must be prepared to change your original plan. You must be prepared to improvise. You will probably not have all of the modern instruments that you use at home.

If you have been in practice for 30 years, as I have, you may find that you must rely on surgical techniques that you largely discarded as newer techniques in plastic surgery were developed.

The scramble to re-create the vital anesthetic happened four years ago, but I still hear from Dr. St. Fleur. Just this past August, I received an email in which he said, “I hope you still remember me. We met in Hôpital Sacré Coeur of Milot. You kindly helped me taking care of patients and taught me so many things. . . Thanks again!” That is precisely the experience that keeps me returning to Milot.

Dr. Peter Kelly and Hope Carter introduced me to CRUDEM during a 2007 Order of Malta pilgrimage to the Holy Land. When I returned to Washington, D.C., I was introduced to Dr. Dick Perry, who was leading a team to Hôpital Sacré Coeur in February 2008. I signed on with Dr. Perry and Dr. Joe Giere as part of a general medical team.

Unsure of what to expect, I experienced a “rollercoaster of emotions”—as I characterize the common reaction of most volunteers on their first medical missions to Milot.

First you want to cry. If you have never been to a third world country, you simply can’t imagine the conditions. Then you suddenly find yourself uplifted by the joy and resilience you find in most Haitian physicians, nurses and patients. By midweek, you become dismayed again. You begin asking yourself, “Can I possibly make a difference here? The challenges in Haiti are so big that I don’t think that one person can even put a dent in it.”

But then you have an experience with a dedicated Haitian physician like Dr. St. Fleur, and it’s clear that you are not there to “fix Haiti”. You are there to help individual Haitians. Sometimes it is another physician or nurse. Sometimes it is a patient. Sometimes it is one or two people a day. Other times, it is many more.

But it is not about the numbers. Rather it is about teaching the hospital staff and learning from them. It is about taking care of the sick and injured on an individual basis. That is what keeps me returning to Sacré Coeur.

After my initial trip, I organized a number of plastic surgery missions with small teams of five or six medical personnel and two to four non-medical volunteers. In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, the medial teams grew, and Dr. Andrew Umhau, a Washington D.C. internist, and I co-led a multi-specialty teams that included plastic surgery, general surgery, anesthesia, internal medicine, pediatrics, intensive care and emergency medicine, specialty nurses, physicians’ assistants, medical and premedical students, and some non-medical volunteers.

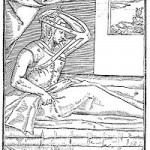

The term, “plastic surgery,” comes from the Greek “plastikos,” which means to form or to shape. Gaspare Tagliocozzi, professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Bologna, published De curtorumchirurgia in 1597, and is considered by some to be the “father of plastic and reconstructive surgery.” He developed a technique of transferring upper arm skin to repair an amputated nasal tip. Victors in war often amputated the noses of those they conquered, so this was not an unusual deformity.

In Haiti, where we do not have equipment such as operating microscopes and the specialized instruments necessary for these types of procedures, we must sometimes fall back on the principles first elucidated by Tagliocozzi.

Tagliacozzi published 47 pages of illustrations and guidelines for reconstructive surgery. It is the first published work on plastic surgery. His method required that the arm be sewn to the forehead for a number of weeks to allow the tissue needed for reconstruction of the nose to develop a blood supply. The arm could later be cut free leaving the tissue necessary to reconstruct the nose on the forehead. This was called an “attached flap”.

This shows a device made from leather straps, which immobilized the arm to the forehead. This is one of the best-known illustrations in the history of plastic surgery.

This shows a device made from leather straps, which immobilized the arm to the forehead. This is one of the best-known illustrations in the history of plastic surgery.

Today most reconstructions can be achieved without such drastic measures. We know much more about the blood supply of all areas of the body, so that we can usually find tissue nearby that can be used. If there are situations where there is no nearby “donor tissue” the development of “micro vascular surgery” in the seventies and eighties allowed us to take expendable tissue from farther away and move it in one stage to an area of injury or deformity using an operating microscope to reestablish blood flow by sewing small blood vessels together.

But last June in Milot, Tagliacozzi’s counsel came in handy when we saw a young man who had been burned badly on his foot. Because Haiti has no burn unit there are very few medical facilities capable of caring for these devastating injuries, the patient had a crippling burn scar deformity of his foot with his toes pointing straight into the air making it difficult to walk and impossible for him to wear normal shoes.

The young man with a badly scared foot and severe deformity of the toes.<

Our Team removed all of the scar tissue and replaced it with healthy skin, and, in the process, straightened the toes. We did not have an operating microscope so we took tissue from his opposite leg and sewed his legs together.

The young man with a badly scared foot and severe deformity of the toes.<

Our Team removed all of the scar tissue and replaced it with healthy skin, and, in the process, straightened the toes. We did not have an operating microscope so we took tissue from his opposite leg and sewed his legs together.

This shows healthy skin taken from the calf of the opposite leg being attached to the injured foot after the scar tissues had been removed and the toes straightened. The area on the back of the calf where the skin is taken can be easily repaired with a skin graft.

This shows healthy skin taken from the calf of the opposite leg being attached to the injured foot after the scar tissues had been removed and the toes straightened. The area on the back of the calf where the skin is taken can be easily repaired with a skin graft.

It would be necessary for him to stay in this position for the next three weeks to allow the skin to heal. To help the patient, we devised our own Tagliocozzi-type device using modern fiberglass cast materials to hold his legs together for three weeks, while the new skin grew to the injured leg. His legs were separated by Dr. Jerry Bernard, the young Hôpital Sacré Coeur general surgeon, after we returned home.

The patient with our Tagliocozzi type of immobilizer, made of modern fiberglass cast materials<

The basic principles of “cross leg flaps” were developed in the sixteenth century. They were refined over centuries, particularly by surgeons caring for patients during the two world wars of the 20th century. In the seventies, after the development of microsurgery, these “cross leg flaps” were generally thought to be “of historical interest only.” But in Haiti, we must sometimes turn back the surgical clock and rely on these tried and true principles.

Each time I return to Hôpital Sacré Coeur, I confront the devastating effects of burns, and the scars they leave behind. In Haiti, most people cook over open fires, so burns are very common. An important goal of my past medical missions is to teach the hospital staff how to provide medical care for patients with burns.

During recent trips, I have lectured about the treatment of burns (See photo Lecture: lecturing the Haitian physicians at Sacré Coeur on the subject of burn treatment).Thus, I was relieved and overjoyed when I learned that the hospital hopes to include a burn unit in its expansion project. Haiti desperately needs a burn unit to care for patients with acute burns, as well as a reconstructive and rehabilitation unit to address the after effects of these devastating injuries.

Tagliocozzi advised that we “repair what has been damaged or lost due to injury or disease.” This includes the deformities caused by birth defects and tumors that occur in many parts of the body. Plastic surgeons focus on birth defects around the head and neck. We nearly always see children with cleft lip deformity, and we are able to employ our skills to make a life long difference in a relatively short, safe and straightforward operation.

The patient with our Tagliocozzi type of immobilizer, made of modern fiberglass cast materials<

The basic principles of “cross leg flaps” were developed in the sixteenth century. They were refined over centuries, particularly by surgeons caring for patients during the two world wars of the 20th century. In the seventies, after the development of microsurgery, these “cross leg flaps” were generally thought to be “of historical interest only.” But in Haiti, we must sometimes turn back the surgical clock and rely on these tried and true principles.

Each time I return to Hôpital Sacré Coeur, I confront the devastating effects of burns, and the scars they leave behind. In Haiti, most people cook over open fires, so burns are very common. An important goal of my past medical missions is to teach the hospital staff how to provide medical care for patients with burns.

During recent trips, I have lectured about the treatment of burns (See photo Lecture: lecturing the Haitian physicians at Sacré Coeur on the subject of burn treatment).Thus, I was relieved and overjoyed when I learned that the hospital hopes to include a burn unit in its expansion project. Haiti desperately needs a burn unit to care for patients with acute burns, as well as a reconstructive and rehabilitation unit to address the after effects of these devastating injuries.

Tagliocozzi advised that we “repair what has been damaged or lost due to injury or disease.” This includes the deformities caused by birth defects and tumors that occur in many parts of the body. Plastic surgeons focus on birth defects around the head and neck. We nearly always see children with cleft lip deformity, and we are able to employ our skills to make a life long difference in a relatively short, safe and straightforward operation.

|

|

In Haiti, it often seems that tumors grow to unusually large sizes. When children are involved, the removal of these tumors poses significant challenges, and our teams have been fortunate to have excellent pediatric anesthesiologists. Without Drs Ben Lee from Johns Hopkins and Marjorie Brennan from Children’s National Medical center in Washington D.C., we would be severely limited in our ability to help children.

During one medical mission completed just three days before the 2010 earthquake, we saw a 5 month old infant with a tumor– growing rapidly since birth–on the back of his head. The x-ray revealed the large tumor attached to the skull and probably communicating with the inside of the skull. Dr. Lee and I both thought that we needed neurosurgical consultation before tackling this. Unfortunately, we did not have a neurosurgeon with us, nor was there one anywhere nearby.

As opposed to using sixteenth century principles, we fast forwarded to twenty-first century technology and took a picture of the child and the x-ray with a cell phone. The image was sent to a neurosurgeon colleague of Dr. Lee’s at Johns Hopkins. Dr. George Jallo–professor of neurologic surgery, pediatrics, and oncology at Johns Hopkins–responded within a couple of hours, even though we sent the photos at 10 o’clock at night. He gave us the necessary advice and support, and we were able to perform the surgery the next morning.

The child and x-ray before surgery and resting comfortably with his mother after successful removal of the tumor

Once again, because of the excellent HSC surgical staff and nursing staff, we knew that the general surgeon, Dr Jerry Bernard, pediatricians and other HSC staff would be able to provide the follow care that the child needed.

As I noted earlier, many plastic surgery techniques were developed as a result of treating wounded soldiers. And I prepare for a mission to Haiti, I often feel as though I am preparing for a battle. We must expect the unexpected. We must plan extensively and meticulously. And at the same time, we must accept that after our arrival, we may have to drastically change our plans. However, none of that effort is wasted, for had we not taken the time to develop an exhaustive plan, we would not be able to revise it, nor make a new one as needed.

As we prepare for future trips—particularly for medial volunteers planning their first mission to Milot–I pass on two reflections that I latched onto while reading about the D-Day invasion during the Second World War. The first is from Dwight Eisenhower. The second has been attributed to several different people, but I always thought that it came from Omar Bradley. Eisenhower advised that “In war, plans are useless but planning is essential.” And the remark I attribute to Bradley is this: “after the first shot is fired nothing goes according to plan.”

In Haiti, we simultaneously rely on age-old surgical principles and modern technology. But the real value of the missions is our person-to-person interactions. We stay focused on the Haitian people and commit ourselves to helping one man, woman or child at a time. As I reflect on our many missions to Haiti, I better understand St. Francis of Assisi when he prayed, “. . . it is in giving that you receive.” When I return home, it feels as if I benefited much more than any of the patients I have treated. Actually, volunteer Jan Willison, a recovery room nurse from Georgetown University Hospital, sums it up best in an email sent after our June, 2011 mission: “Heat, sweat, and tears. . . Haiti. I’ll go back in a heartbeat with you. Thank you to all the team who made it the very best. Sign me up for next time! I am forever changed.”

Albert Fenwick Fleury, Jr, MD is a graduate Georgetown Medical School; Clinical Associate Professor in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Georgetown University Hospital; plastic and reconstructive surgeon in private practice in Washington, DC; husband of Mimi Fleury, DM and father of three sons.

Joan Frawley Desmond, a Dame of Malta, is a senior editor for the National Catholic Register. She resides in Chevy Chase, MD with her family.