By Harry C. Sax, M.D.

“A Jewish surgeon who grew up in a Kosher household, participates in a Mass led by an Irish Catholic nun who delivered babies in rural Africa, in a chapel restored by a Canadian Protestant youth group, and later shares a cool drink with an Islamic Turkish soldier from the UN, while a Creole funeral fills the streets outside the gates of a hospital built by the Order of Malta.”

Although it sounds like the beginning of a great joke, it is everyday reality at Hôpital Sacré Coeur. My experiences in Milot often included paradigms like the one above. What brought all these disparate groups together? And more importantly, what was the common bond that allowed them to function effectively and synergistically? How did it make me look at my own religious experiences and prejudices? In many other locations in the world, the same ethnic groups are in conflict over their religions.

I would suggest that despite our individual beliefs, we were all feeling a higher level of oneness with ourselves and our true values – a transcendent sense of spirituality. And despite a religious upbringing, it was the time in Milot that brought me to that understanding. I grew up in a very traditional Jewish home in a steel town in northeastern Ohio. My parents were first generation American and my father had served in World War II, observing firsthand the horrors of the concentration camps and the Holocaust.

They remembered quotas and movies like “The Gentlemen’s Agreement.” Although not overtly paranoid, it was made clear to me that as a Jew, I was different from “the others.” We followed the dietary laws, I learned Hebrew, had a Bar Mitzvah, and at one point considered becoming a rabbi. Yet, I saw traditional Jewish law as a series of what you shouldn’t do, rather than what you should. Each year at the High Holidays, I would recite the sins in the “Al Chait” without realizing the nuances of a group confession and an acceptance of our own vulnerabilities – and potential for change.

Our youth group raised my social consciousness – there was the first Earth Day, the US was still involved in the Viet Nam War, and Israel was rebuilding after attacks in both 1967 and 1973. Our work was local and the concept of “Tikun Olam” – repairing the world, was introduced. I slowly began to see religion as a way to strive to better one’s self, while reaching out to others.

Our youth group raised my social consciousness – there was the first Earth Day, the US was still involved in the Viet Nam War, and Israel was rebuilding after attacks in both 1967 and 1973. Our work was local and the concept of “Tikun Olam” – repairing the world, was introduced. I slowly began to see religion as a way to strive to better one’s self, while reaching out to others.

Rules and laws had deeper meaning, and a commonality with other religions and their traditions began to emerge.

Then there was college, medical school, and surgery residency.

Religion and spirituality became buried in the overwhelming intensity of the process. I did marry a Jewish woman, who was from the Deep South and had her own experiences with feeling different. I never truly experienced my Judaism. When we had children, we realized that there was a responsibility to teach them about their heritage and values. Our first child was a boy – so of course – do you have a “bris,” the ceremonial circumcision? We questioned the medical versus the religious, and found a compromise that worked for us.

Realizing that there was comfort to families in having a physician do the procedure, and looking for a way to understand my own religion better, I subsequently became a mohel. I was able to combine my surgical skills with providing a positive religious experience to new parents, and hopefully their 8 day old son.

At the end of the ceremony, I would recite the Priestly benediction.

“May God bless you and keep you”

“May God cause his face to shine upon you and be gracious unto you.”

“May God lift up his countenance unto you, and grant you Shalom.”

I always choke up on the last part – we are all searching for Peace – within and outwardly.

When I first arrived in Milot after the quake, I was in a pure clinical mode. Didn’t feel like my religion made a difference, and in fact, I kept it quiet, (although I did secretly look at who didn’t cross themselves at evening prayers.) Over the ensuing three weeks, I found myself more open to the feeling of flow that would overtake me in the middle of chaos. I watched Sr. Ann’s smile as she danced with the amputee children, holding them aloft, and I truly understood spirituality when I returned from town one day and one of the pediatricians was looking for me.

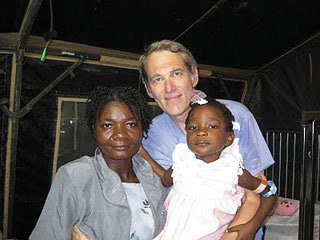

Amidst the chaos of traumatic injuries, a 4 year old girl was brought in by her mother.

Her abdomen was massively distended, and she had stopped eating. Our sole imaging was ultrasound, and we saw a giant mass with both fluid and solid components. The only way to diagnose and potentially treat her was an operation. I had not operated on a child in more than a decade. Speaking to her mother through a translator, I said that I did not know what was in her abdomen. She handed me her daughter.

Her abdomen was massively distended, and she had stopped eating. Our sole imaging was ultrasound, and we saw a giant mass with both fluid and solid components. The only way to diagnose and potentially treat her was an operation. I had not operated on a child in more than a decade. Speaking to her mother through a translator, I said that I did not know what was in her abdomen. She handed me her daughter.

“Jesus knows.”

The next morning, working with one of our HSC gynecologists, I opened the child and was able to completely remove her ovarian mass, preserving the other side. She went home 3 days later. The enclosed picture is still one of my screen savers. Jesus must have been looking over the shoulder of this Jewish surgeon that day.

It is a Jewish saving that “to save one life is to save the world.” And at HSC, I now have the opportunity to combine my training for a procedure in the Jewish tradition with reducing the spread of AIDS in Haiti.

Recent scientific data have shown that circumcision is one of the most effective ways to reduce transmission of HIV. The science behind it is real and compelling. So when young men being seen for a hernia or hydrocele repair ask me if I can do “a little snipping,” I smile. There is the thought in the community that circumcision may improve the sexual experience, and I’m fine with that. Perhaps there is also a greater power at play.

Recent scientific data have shown that circumcision is one of the most effective ways to reduce transmission of HIV. The science behind it is real and compelling. So when young men being seen for a hernia or hydrocele repair ask me if I can do “a little snipping,” I smile. There is the thought in the community that circumcision may improve the sexual experience, and I’m fine with that. Perhaps there is also a greater power at play.

With every trip to Milot, I gain a greater appreciation that the religious overlay, in this case Catholicism, creates a lattice to which we each add our own experiences, beliefs, and core values. On stepping back, the individual traditions have fused into something larger, something that we define as spirituality. Organized religions try to place the lessons of the past into a structure that is relevant for today. The similarities and differences can crystalize important questions. Many of my Jewish friends dated and married Catholics. I always thought it was shared guilt. But it wasn’t until I immersed myself into a Catholic organization performing Tikun Olam, that I grew closer to my Jewish roots.

. . . and since I work in Los Angeles, I’m thinking about a new series “The Mohel of Milot”

Jerry Seinfeld, are you listening?

Harry Sax, M.D. is Vice Chair of Surgery, Physician Liaison Cedars Medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Sax received his MD from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and received additional training at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and University of Rochester School of Medicine & Dentistry. He is a graduate of the Health Care Management Program at Harvard University School of Public Health. Dr. Sax makes frequent volunteer medical missions to HSC. An avid pilot, in his spare time, Dr. Sax flies volunteer missions for the California Wing of the Civil Air Patrol.

Harry Sax, M.D. is Vice Chair of Surgery, Physician Liaison Cedars Medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Sax received his MD from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and received additional training at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and University of Rochester School of Medicine & Dentistry. He is a graduate of the Health Care Management Program at Harvard University School of Public Health. Dr. Sax makes frequent volunteer medical missions to HSC. An avid pilot, in his spare time, Dr. Sax flies volunteer missions for the California Wing of the Civil Air Patrol.