One Surgeon’s Reflections on a Decade of Volunteering at HSC

Each year, when I return from Hôpital Sacré Coeur (HSC), I face the same daunting task: how to describe and explain Haiti to those who are curious, but not lucky enough, to experience this wonderful and mysterious place? The questions are simple enough: What is it like? Are things getting better? And perhaps the most common: What is wrong with Haiti? I would like to answer, but it is a monumental task.

I try words and pictures. Not much success there. I offer simple quips to suggest the complexity of the issues and our ambivalent emotions: “We can’t wait to get there; we can’t wait to leave!” I think, in the end, we cannot explain Haiti because we do not understand it ourselves. Part of the issue, I suppose, is the need to immerse all of your senses — smell, taste, sight, touch and hearing — in the experience. But despite our best efforts, Haiti remains a thing apart, unknown. We remain visitors, though frequent ones. Even those who come back year after year must be content with impressions of Haiti; few would claim to know it.

After 10 years, I am beginning to realize that some of the difficulty is driven by our view of Haiti as a static object.

As one-week visitors, we are always on the outside, looking in. We tend to see what we expect. In striving for a description, we forget to include our presence and our interactions. Is Haiti and HSC a place, or is it a relationship? Can we describe Haiti if “it” is always “them”?

Which led me to this recent insight: we must first understand “us” before we can understand “them.”

If we could understand ourselves, we could perhaps explore the relationship of the volunteers to the Haitian staff as a means to understanding Haiti and HSC. Just how do we — the volunteers — fit in to the big picture? Why do we go to Haiti? How do the Haitians benefit? And where is this all headed? It used to seem pretty obvious to me, but as often happens in life, it is not so clear anymore. Like a long term marriage, Haiti, HSC and us — the volunteers — are in a constant state of change.

Why do we volunteer? There are lots of ways to say it, but fundamentally volunteering satisfies our desire to help our fellow man. Our experience tells us there is no greater reward than the one-on-one human connection of helping a patient. In addition, our mission is to teach, and ultimately to transition patient care to the staff of HSC. But the intoxicating reward of direct care is an addictive substitute for the elusive goal of transitioning care to others. We tell ourselves that change comes slowly in Haiti; there seem to be so many obstacles.

I have no clear vision just how this transition would happen. In struggling to see this future, I think of the brief response Muhammad Ali gave, at a Harvard Commencement, to a request for a poem: He said simply, “Me…We”.

But how to get from Me to We? With enough understanding on both sides, can we get beyond “us” and “them” to become We?

History

HSC began in response to a request to Brother Yves from the people of Milot for a medical clinic. Dr. Ted Dubuque — a surgeon — answered that call, and for many years was the only provider of care to the area. His mission was clear and challenging. I suspect that Ted Dubuque remains the inspiration for most of us volunteers. But the HSC of Dr. Dubuque’s day bears little resemblance to the hospital we volunteer at today. There is now a Haitian staff — an excellent one — to provide care that was non-existent in 1986. And yet, there are more volunteers than ever. So why do we continue to come? Some very special volunteers, like Dr. Kyley Wood, (see Bon Nouvèl, Winter 2014) provide a service not available anywhere in Haiti. But most of us are supplementing very high quality care, so we must ask, “How do the Haitians benefit? Where do we fit in the big picture?” I will give you my own story, spanning a brief 10 years, to highlight the enormity of the evolution of HSC.

Surgeons

Part of understanding this dynamic is understanding the volunteers. We are for the most part surgeons, and surgeons are action people. We like to get things done, and there is an easy way of measuring this: counting your cases. How many cases did you do in internship? Residency? How many per year now? There are really only two types of surgeons: those that keep meticulous records of all their cases, and those who wish they did. In Haiti, this is also the way we “value” our services: how many cases we did in our week. The more cases, the more value. The more cases, the better we feel. Who could argue? But what about that goal of transitioning care to the Haitian staff? Deep down, I suspect we all would like to see HSC become much like our hospitals here at home. Our ultimate goal is to reduce our need to volunteer. As the Haitian staff has grown both in quality and quantity, is our volunteering now driven by our needs? How do we get from Me to We?

Surviving and Thriving in Haiti

Again, to understand Me, I reflect on my early experience. My first visit to HSC was both emotionally traumatic and incredibly rewarding. It was apparent that the need for surgeons was gigantic. There was no full-time general surgeon on staff and there had not been a volunteer general surgeon there in months. It seemed to me that there would always be a need for us in Haiti. First time volunteers are always bug-eyed at what they experience in Haiti, and even the currently well-functioning HSC leads the initiate to ponder all the things that could make Haiti better. Their heads spin with big ideas and short time frames. I was no different. Yet I knew I was not Ted Dubuque; I learned early on that — unless I was willing to stay for 6 months, learn the Haitian language, and gain the trust of the staff — it was best for all concerned if I just went with the flow.

Charley Stackhouse and I would arrive yearly, set our expectations to “Haitian”, and do what we could. We loved and respected the staff, deeply appreciated the patients, and enjoyed our week. We counted cases. But as the years went by, things were changing around us.

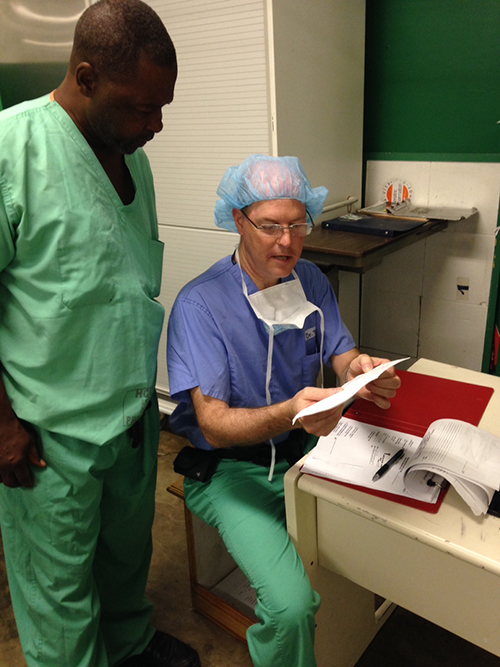

By our 5th visit, we had a very welcome surprise: Dr. Jerry Bernard, the first full-time Haitian general surgeon at HSC, arrived mid-week. He was awesome!

We loved Jerry, and were extremely impressed with his surgical skills. We were even more impressed with his bedside manner and compassion.

We enjoyed working with Jerry, but the reality was that we and Jerry had workloads that seemed to limit collaboration and education. We had a full — often over full — OR schedule, and Jerry had night call, consults etc.

The upside of “going with the flow” was the promise of a very tiring but very enjoyable and rewarding yearly visit. But over the ensuing years, the downside was becoming apparent: despite two ‘teams’ — Haitian and American — our goal of WE seemed as far away as ever.

By acquiescing to what I understood to be the “Haitian Way”, I was abdicating my role in a process of change. I was perpetuating and encouraging the concept of us and them. I was content — really, quite pleased — with doing cases.

Since the earthquake, I sense another issue arising: the hospital has an increasing reputation, both locally and regionally; perhaps nationally. Our patients seem to come from farther and farther away. More disquieting is a sense that some patients come to see “the American doctors.” My earlier questions — “How do the Haitians benefit? Where do we fit in the big picture?” — are driven in part by this concern. Are patients bypassing Haitian hospitals to get to the “Haitian-American” hospital? And yet, there seems to be so much surgery to do. I could not envision our role as volunteers ever ending, or even changing. I was content to take care of the patient in front of me.

My Enlightenment

Then last year, I met two people who introduced me to a new way of thinking. Dr. Robert Jarrett, founder of Hearts Around the World, and Dr. Catherine deVries, founder of IVUmed, each with extensive experience in global medicine. Jarrett and deVries built organizations based on teaching, not doing.

In discussing the volunteer experience, their collective experience and successes led me to question my two core concepts about volunteering: Go with the Flow, and Helping More by Doing More. It was time to reevaluate my role as a volunteer. My timing could not have been better. I could not conceive of how the addictive rewards of volunteering could be pushing the goal of “We” off into the future.

I like to tell people that doctors are quite lucky to have transportable skills. There is so much work to do in developing countries, and we can get off a plane and step right in. Yet at the same time, we meet volunteers who come to Haiti to build, for example, a church, and ask ourselves, “Why are they doing the building?” I never considered that our volunteering might be more similar than we care to admit.

So much of life is serendipity, and this was the perfect time for CRUDEM to gain their first CEO, Mike Maron. Mike is not a Haiti veteran, and has none of my impressions (now perhaps becoming prejudices) of the way things are done in Haiti. He did what very few of the volunteers have time to do: over the course of a year, Mike devoted himself to listening and learning from our Haitian partners. Mike did not look for what “he” could do, but what “we” could accomplish. Far from “going with the flow,” he sought to understand how things are done. Where I accepted “the Haitian way,” Mike — it seems to me — asked “Why? Is there a better way? Is this getting us to our goal?”

In response, the outstanding Haitian leadership team headed by Dr. Harold Prévil has blossomed, transforming HSC into the sort of place that, ironically, we volunteers had always envisioned.

Fast forward to our annual Spring visit: We always note some incremental changes at HSC, but these are mainly physical. The “mood” of the hospital has always been quite predictable. We were, as they say, on Haitian time, and had no problem with that. Culture change, I anticipated, would take a decade or more. More I guess, because I had already been coming for a decade! I was never sure how change would occur, but I was sure it would be slow to happen.

But in fact we had a quite remarkable week — like none before. Instead of Haitians and Americans working separately, we were suddenly, and pleasantly, part of one organization. Just like that. I have some anecdotes to illustrate my point:

As is the case with all volunteer teams, we arrive on Saturday morning, and head straight to clinic. Our flight is late; the patients and staff have been waiting for hours by the time we arrive. The staff’s weekend off is shrinking by the hour. It is a VERY busy clinic — 75 patients — and we have a new surgeon on our team. It is going to be a long afternoon. From my experience, I know the staff gets a little frustrated as the day wears on. But when I express my concern to one of the nurses, she replies with a smile, “We’re doing fine, don’t worry.”

A busy clinic leads to a heavy surgical load. I think we are unlikely to see or work with the Haitian surgical staff very much. My first patient Monday morning is actually a patient of Dr. Richard Toussaint, a new HSC general surgeon, whom we had briefly met last year. That is, we did not see the patient in our clinic, and thus, I am scrambling to see what the case is about, history, physical etc. I am a little miffed. Shortly after beginning the case, Richard scrubs in to join me. Surprised to see him, I apologize for doing “his” case. “It is not ‘my’ case”, he replies. “It is ‘our’ case.” We did many cases together that week — to both of our benefits. Me…We

Thursday, we are a little tardy arriving to the OR, knowing things never start on time. We are met by our Haitian anesthesiologist, saying the patients are in the rooms, and could we get started?

Mid-week, I receive an email from an American nurse, working with a nearby NGO, asking if we (i.e. the American doctors) would see a Haitian patient who works for them. After a long exchange of emails suggesting the patient would be best served by seeing our Haitian Gynecology colleagues, not us, she relents. But I am again disturbed that our excellent hospital is seen as the place where you can see American doctors. As I discuss this with a member of the Haitian staff, he says, “You know, we are now a Team here. We all work together. Not everyone buys in, but those that stay are a Team.”

I had NEVER seen ANY organization ANYWHERE turn its culture around this fast. We had a great week of teaching and learning. A great week of WE.

How did this happen and why was I so surprised?

I can only offer conjecture as to how this sea of change occurred. The fact that it surprised me indicates that Mike Maron simply did not see what many of us see. Mike did not see Haitians — he saw hardworking people. He ignored apparent evidence of a “failed state” and saw glowing opportunity. He expected success instead of the status quo. He did not buy into the disabling belief in a “Haitian Way.” Simply put, Mike did not seem to cross any borders at all when he entered Haiti.

And the changes were all developed and implemented by a Haitian executive staff that I knew well. I suspect much of the unleashed energy had been building for quite some time. The chemistry between two CEOs, Mike Maron and Harold Prévil, was powerful enough to ignite a whole new vision in 12 months. Me…We

Now perhaps I am on thin ice — but I wonder: could the historical dependence on volunteers have been delaying some of this progress? We are, after all, a stream of benefactors, constantly coming and going. Because we are viewed — and see ourselves — as benefactors, we are treated and act differently. Our trips are approved and arranged by a state-side NGO — CRUDEM. We get three meals a day, our own living quarters. Do we behave differently in this role, than if we were visiting a state-side hospital? At the end of the day, if I am a reasonable example, as long as my expectations (a busy schedule) are met, I am satisfied. In fact, I enjoy the exotic and different aspects of working at HSC. Not really a formula for driving change.

What did I learn?

I learned that the adage “you get more than you give” when volunteering is true. And this can lead to problems! I learned we can all behave with the colonialist instinct of “we know best.”

I learned that, in relationships, you are always sending messages. This is perhaps even more so when you are a stranger in a strange land. I learned that you do indeed have to know yourself before you can know others.

Perhaps most of all, I learned that what I perceived as an immutable Haitian Culture does not exist; that developing countries have as much potential and enthusiasm for change as we do. Maybe more. And that a little facilitation is worth more than a lot of doing.

Oh…and I now I find it much easier to explain Haiti!

Dr. Brady is a mostly retired general surgeon from Canandaigua, NY. He is very grateful to be a tiny part of the great work done by CRUDEM and Hôpital Sacré Coeur.