Chapter excerpt from the book, In the Valley of Atibon printed with permission from the author.

Pastor Jasmin told me about the death of Victoire, wife of our Security Chief, Ivon. She had been ill for a long time. Diabetic, her gangrenous leg had been amputated below the knee four or five years before, but she suffered constantly from pain in her phantom leg. He guessed she had contracted cancer, too, and finally she died, and Pastor Jasmin invited me to his church for the service.

On my way to the church I stopped at Sabael Paul’s little gingerbread house. He had just retired as manager of Medical Records, so I was very happy to see him again. Dressed in a long-sleeved white shirt, tie and suit trousers, Sabael held court to neighbors and family on his porch. He kissed me on both cheeks and put his arm around my waist, introducing me as the “gwo chef opital — big hospital chief.”

“Zanmi ou” — “Your friend,” I amended.

We heard a brass band approaching and leaned out toward the road where a procession of musicians approached dressed in white shirts and black trousers playing “Auld Lang Syne” in New Orleans-style on trumpets, trombones, saxophones and drums.

“Ah,” Sabael chuckled.

“Ah,” Sabael chuckled.

“People do like a good funeral!”

A fact that had appalled Dr. Mellon, by the way. He thought it a terrible waste of money to hold vigils for days on end, during which food and drink had to be provided for countless mourners. Morgue fees would mount daily as families awaited kin to arrive for the funeral, often from the United States. Families begged, borrowed or stole money to propitiate the loved one’s spirit and show up their neighbors, believing that the fancier the coffin the happier the soul, and the more respected the family would be. Dr. Mellon thought simple, inexpensive burials should be the norm among poor people, and he tried to set an example by being buried in a cardboard coffin the day after he died, with no vigil or fanfare. People were mystified that such a rich man would not have a magnificent funeral, and they never understood the point of his humble burial.

As the band passed Sabael’s house, he donned his suit jacket, dusted off his bowler hat, settled it onto his mat of white hair, and we stepped out onto the road. He held my hand in his big mitt as we walked to the church.

As the band passed Sabael’s house, he donned his suit jacket, dusted off his bowler hat, settled it onto his mat of white hair, and we stepped out onto the road. He held my hand in his big mitt as we walked to the church.

I was more than a little touched by his friendship and by his well-dressed form next to me as we sat side by side in a rough-hewn pew. The church’s cement walls were festooned with paper decorations hanging on strings across the bare rafters, and pasted on all the walls were admonitions: “This is the temple of the Lord, Be Silent!,” “Jerusalem lives,” “Bethel — May the Children Obey!” “Everyone Welcome.”

Madame Ivon’s ornate silver coffin with a domed lid lay open at the front of the church. People crowded up to peer in, women screamed and ululated, jumping up and down, twisting their hands in the air. Finally, everyone settled down. Only the deceased’s sister in the front pew continued to moan in a perfect blues cadence, “What shall I do now that she’s don/ M pa konne, M p konne.” I don’t know, I don’t know.

An electric keyboard squealed an opening hymn that the congregation sang heartily. Three other pastors preached for half an hour or more. Suddenly, I heard a loud snort. Ladies in front of us turned around to level indignant stares at Sabael, whose chin had sunk to his chest. I stifled a giggle, remembering how, when he was still working, I would find him at his desk, slumped in his big chair snoring, while his young staff tip-toed respectfully around their chief.

Pastor Jasmin finally approached the pulpit and got to the heart of the matter, Madame Victoire’s life. Born June 16, 1933, she was, perhaps, the most beautiful woman in Deschapelles. With her light skin, always well dressed, she walked proudly through town. When Ivon met her in 1975 she belonged to another man, but she “te revokay li — fired him” — and took up with a Monsieur Desira. After a time she fired him, too, and went to Ivon, then fired Ivon and went back to Desira, eventually returning one again to spend her last years with Ivon.

Jasmin, who knew that she practiced Voudou, had been trying for years to persuade her to come to Jesus. Madame Victoire joined the Seventh Day Adventists for a time, and vacillated between that church and Voudou. In her last years, however, Jasmin said that Victoire was “hit in the brain,” a stroke perhaps, and her mind went. Ivon carried her back and forth to the hospital, but the doctors said there was nothing wrong with her that they could see. “An ryen! Nothing!”

Jasmin relentlessly tried to reach the dim corners of Madame Victoire’s mind, and finally achieved victory. She accepted Jesus. “And Jesus, who forgives all, will take you to his bosom at the last minute, even if you have denied him all your life,” Jasmin boomed. “What is man before death? An ryen!” He waved towards the coffin. “Even this flower, too long in the sun, goes back to the earth. An ryen!”

As the service ended and we left our pew, I did not see Ivon. I asked Sabael where he was. “He could not leave his house,” he whispered. “He is too desolay — too depressed.”

I had seen Ivon in the hospital corridor the morning after his wife died and he burst into violent as sobs as he told me. I put my arms around him and patted his shoulder. My heart went out to Ivon when I heard he was too prostrate to attend Victoire’s funeral, but I later learned that the final vigil the night before was fraught with rum-drinking, dancing and singing until dawn and that Ivon, when he went to claim his wife’s body from the hospital morgue to load it into a pick-up truck that morning, had passed out on the steps.

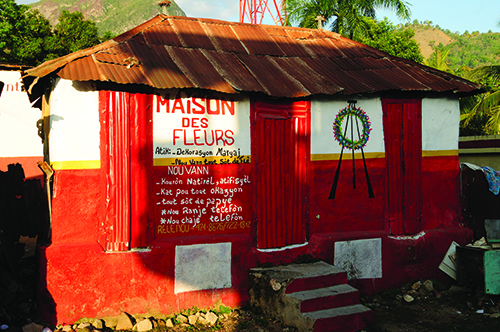

A cortege of fifty people followed the pick-up truck that carried the coffin and the pallbearers past Ivon’s house. Was he lying in his bed listening, lamenting, longing or merely sleeping it off? We slowly marched behind the brass band down the rocky path around the HAS grounds and skirted the canals through fields where little houses nestled in shady groves and children stood gaping at the procession. At last we arrived at the cemetery of Deyebwa — Back-of-the-woods. The noon sun burned through the clear sky; the only clouds were of dust that rose in our footsteps. Seat puddle in the creases of Sabael’s face and wilted his shirt collar as he walked more and more slowly, his small feet shod in elegant black shoes. Not one man took off his jacket in the pounding heat. The band led us to a colony of crypts, each decorated with ornate masonry on peaked roofs with sculpted facades. We approached a mausoleum with two shoulder-high doors, one plastered over, the other gaping open. I peered in and saw another coffin pushed to the back of the vault, presumably a member of Victoire’s family. The perspiring pall-bearers laid Victoire’s coffin on the ground in front of the crypt and the band blared a hymn while Pastor Jasmin mumbled prayers quickly, anxious to get out of the sun.

A cortege of fifty people followed the pick-up truck that carried the coffin and the pallbearers past Ivon’s house. Was he lying in his bed listening, lamenting, longing or merely sleeping it off? We slowly marched behind the brass band down the rocky path around the HAS grounds and skirted the canals through fields where little houses nestled in shady groves and children stood gaping at the procession. At last we arrived at the cemetery of Deyebwa — Back-of-the-woods. The noon sun burned through the clear sky; the only clouds were of dust that rose in our footsteps. Seat puddle in the creases of Sabael’s face and wilted his shirt collar as he walked more and more slowly, his small feet shod in elegant black shoes. Not one man took off his jacket in the pounding heat. The band led us to a colony of crypts, each decorated with ornate masonry on peaked roofs with sculpted facades. We approached a mausoleum with two shoulder-high doors, one plastered over, the other gaping open. I peered in and saw another coffin pushed to the back of the vault, presumably a member of Victoire’s family. The perspiring pall-bearers laid Victoire’s coffin on the ground in front of the crypt and the band blared a hymn while Pastor Jasmin mumbled prayers quickly, anxious to get out of the sun.

As the band ended the hymn, he signaled to the pall bears. “Okay, mette li dedan. — Put her inside.”

As the band ended the hymn, he signaled to the pall bears. “Okay, mette li dedan. — Put her inside.”

They heaved the coffin to the open door. But the doomed lid would not fit inside the opening! Consternation reigned as people crowded around, giving advice and scolding the pallbearers. A young carpenter produced a hammer and sprang to the coffin, opened it and commenced to rip away the lid from its hinges, while everyone watched approvingly. The carpenter handed the lid to someone, and clapped the dust off his hands. Madame Victoire lay in her open coffin, hands folded on her chest, a lily wilting between her fingers. They shoved her through the door into the dark interior.

Sabael took my arm. “Let’s go. It’s hot.”

The exhausted crowd dispersed quickly, leaving two men mixing cement to seal Madame Victoire into her final dwelling.

Leita Kaldi worked at the United Nations in New York, UNESCO in Paris, at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and Harvard University. She was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Senegal from 1993 to 1996, and wrote a memoir of that time, Roller Skating in the Desert, Kaldi became Administrator of Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in 1997, and retired in 2002.

Leita Kaldi worked at the United Nations in New York, UNESCO in Paris, at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and Harvard University. She was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Senegal from 1993 to 1996, and wrote a memoir of that time, Roller Skating in the Desert, Kaldi became Administrator of Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in 1997, and retired in 2002.