By Katie Traynor, MA.

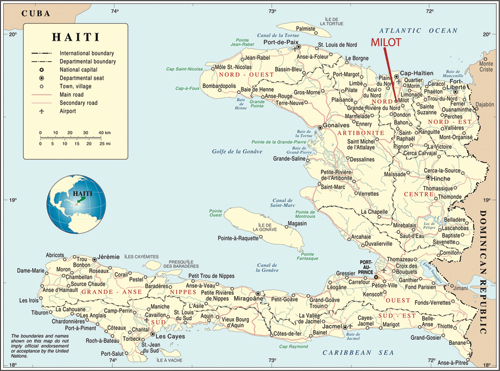

The account of the Haitian people is a narrative of spirit, strength, triumph, apathy, and resignation. Haiti is situated on the island of Hispaniola, located 80 miles southwest of Cuba, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the North and the Caribbean Sea to the south (Arthur, 2007). In its early history, Haiti was a flourishing island and was one of the richest colonies in the world. It was tenanted with thriving plantations and the prosperous exportation of mahogany and sugar, all of which was dependent upon slave labor from the African continent. Today there are over 9 million people living in Haiti, a country with a landmass similar to the State of Maryland. With unemployment approaching 80%, more than half of the population lives on less than one U.S. dollar a day (Arthur). Currently, Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (CIA, 2009). To understand the epic economic downfall of this small country, one must consider the historical progression of events from the first settlers to the present social structure. Charles Arthur’s book, In focus Haiti: A Guide to the People, Politics and Culture, provides an comprehensive assessment of the struggles which the country has endured over time.

In the late 15th century, the Arawaks and Tainos Indians, indigenous peoples who populated most of the Caribbean Islands, inhabited Haiti. The Arawaks were entirely wiped out by both ill treatment borne by their Spanish captors and the spread of European diseases for which they had no natural resistance (Arthur, 2007). The island of Hispaniola remained sparsely populated on the northern and eastern coastline by the Spanish and their African slaves, who were busily establishing and working in a number of sugar cane and cotton plantations. During the 17th century, the French had begun to take interest in the island’s lush and uninhabited western and southern coastlines. Although, France and Spain had often been at odds in their pursuit of colonial empires, in 1795 a treaty between the two countries was signed and Spain ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France. Soon after, the French began importing large numbers of slaves from Africa to establish and operate more plantations and to provide the First French Republic with an economic engine. By the late 1700s, there were almost 500,000 slaves living in the French controlled colony, known then as Saint Domingue, now referred to as Haiti (Arthur). In 1791, the slaves revolted against their French owners. The next 13 years saw other groups of slaves fomenting discontent and mounting insurrections against their masters until in 1804, the French were finally defeated and the slave population successfully gained independence, bringing about an end to slavery within Haiti. It is important to note that most of Haiti’s current population is made up of the descendants of these courageous revolutionaries (Arthur).

In the late 15th century, the Arawaks and Tainos Indians, indigenous peoples who populated most of the Caribbean Islands, inhabited Haiti. The Arawaks were entirely wiped out by both ill treatment borne by their Spanish captors and the spread of European diseases for which they had no natural resistance (Arthur, 2007). The island of Hispaniola remained sparsely populated on the northern and eastern coastline by the Spanish and their African slaves, who were busily establishing and working in a number of sugar cane and cotton plantations. During the 17th century, the French had begun to take interest in the island’s lush and uninhabited western and southern coastlines. Although, France and Spain had often been at odds in their pursuit of colonial empires, in 1795 a treaty between the two countries was signed and Spain ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France. Soon after, the French began importing large numbers of slaves from Africa to establish and operate more plantations and to provide the First French Republic with an economic engine. By the late 1700s, there were almost 500,000 slaves living in the French controlled colony, known then as Saint Domingue, now referred to as Haiti (Arthur). In 1791, the slaves revolted against their French owners. The next 13 years saw other groups of slaves fomenting discontent and mounting insurrections against their masters until in 1804, the French were finally defeated and the slave population successfully gained independence, bringing about an end to slavery within Haiti. It is important to note that most of Haiti’s current population is made up of the descendants of these courageous revolutionaries (Arthur).

After the rebellion, the ex-slaves could not bear to go back to work on the plantations; therefore, the once rich and cultivated land lay fallow (Arthur, 2007). A new order was evolving from within the liberated population; the ascent to authority and governance by the mulatto group who asserted their will over the ethnic black inhabitants. Thus began the split of Haiti’s population. Black peasants were forced to carve out a meager existence on their own small plots of land in rural, mountainous areas while the militant and political elite remained in the cities (Arthur). Those living in the rural areas maintained certain African traditions, practicing Voodoo beliefs and speaking the language of Creole, a mixture of African dialects and French. The urban-based population, many of whom were mulatto as the result of relations between owner and slave, were speaking French and following the practices of the Catholic Church.

After the rebellion, the ex-slaves could not bear to go back to work on the plantations; therefore, the once rich and cultivated land lay fallow (Arthur, 2007). A new order was evolving from within the liberated population; the ascent to authority and governance by the mulatto group who asserted their will over the ethnic black inhabitants. Thus began the split of Haiti’s population. Black peasants were forced to carve out a meager existence on their own small plots of land in rural, mountainous areas while the militant and political elite remained in the cities (Arthur). Those living in the rural areas maintained certain African traditions, practicing Voodoo beliefs and speaking the language of Creole, a mixture of African dialects and French. The urban-based population, many of whom were mulatto as the result of relations between owner and slave, were speaking French and following the practices of the Catholic Church.

Under the rule of the mulatto elite, the 19th century witnessed massive deforestation of the land with the lucrative export of logwood and mahogany to Europe and North America (Arthur, 2007). Wood and charcoal were the main source of energy on the island, and by 1923, three-quarters of Haiti’s trees had disappeared. With the lack of tree cover, the soil eroded and the land became rocky. Currently, Haiti’s land is almost uncultivable, especially in the mountains where famine and drought are a serious threat to the rural population (Arthur). Haiti’s prosperity was short-lived and with no way of using the land for sustenance, the country’s economic downfall began.

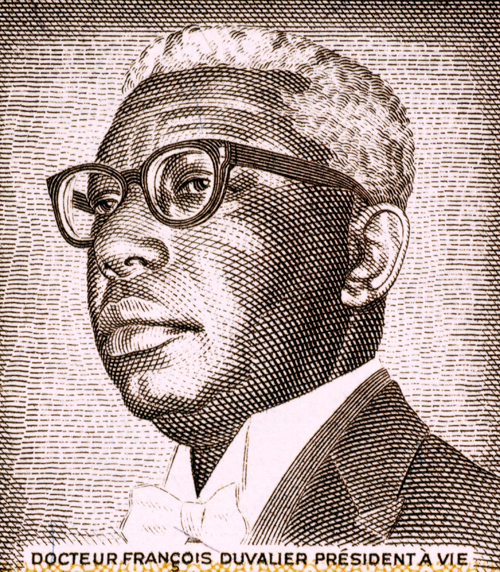

Even though foreign trade had all but disappeared, Haiti’s government continued to revolve around the country’s mulatto elite, revealing the value of hierarchy (Arthur, 2007). The importance of social and economic status is something that successive governments traditionally have either tried to strengthen or destroy during their occupation of authority. In 1957, Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier became president by bridging the gap between the country’s middle class and the poor. Once elected, he mollified his supporters with public works projects financed by the World Bank and began siphoning foreign aid intended to rebuild his country. To protect his interests and quell any opposition, he established a violent, personal militia known as Tonton Macoutes, thus silencing the voice of the Haitian people. The regime put an end to every civil society, workers’ union, political party, and student organization in Haiti, killing more than 3,000 citizens during Duvalier’s brutal consolidation of power (Arthur). A surviving member of one of these besieged groups said that living under the dark shadow cast by Duvalier’s administration was dire. The young student was quoted, saying, “If you had talent or ambition, and wanted to stay in Haiti, you had two alternatives: You could let yourself be totally corrupted, or you could be killed. That was it” (Arthur, 2007, p. 23). The country’s poor grew hopeless and apathetic.

Even though foreign trade had all but disappeared, Haiti’s government continued to revolve around the country’s mulatto elite, revealing the value of hierarchy (Arthur, 2007). The importance of social and economic status is something that successive governments traditionally have either tried to strengthen or destroy during their occupation of authority. In 1957, Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier became president by bridging the gap between the country’s middle class and the poor. Once elected, he mollified his supporters with public works projects financed by the World Bank and began siphoning foreign aid intended to rebuild his country. To protect his interests and quell any opposition, he established a violent, personal militia known as Tonton Macoutes, thus silencing the voice of the Haitian people. The regime put an end to every civil society, workers’ union, political party, and student organization in Haiti, killing more than 3,000 citizens during Duvalier’s brutal consolidation of power (Arthur). A surviving member of one of these besieged groups said that living under the dark shadow cast by Duvalier’s administration was dire. The young student was quoted, saying, “If you had talent or ambition, and wanted to stay in Haiti, you had two alternatives: You could let yourself be totally corrupted, or you could be killed. That was it” (Arthur, 2007, p. 23). The country’s poor grew hopeless and apathetic.

In 1971, “Papa Doc” died and his son, Jean-Claude, “Baby Doc,” continued to administer the country in an even more brutal manner than his father did. Throughout the 70s, “Baby Doc” confiscated foreign aid for himself and his private army, heavily taxed the poor, and destroyed Haiti’s economic infrastructure through corruption and intimidation. During the mid-1980s, Haiti’s poverty-stricken residents united under desperate circumstances with the steeled determination to overthrow their oppressive government. In fear of the repercussions of another revolution, the United States intervened and exiled Duvalier to France in 1986 (Arthur, 2007).

At the end of 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristede became the country’s next president during the largest election in Haitian history. Aristede, a Catholic priest, won 67% of the vote by promising “justice, governmental accountability, and a chance for the population to participate in determining the nation’s future” (Arthur, 2007, p. 25). The result of the election prompted the former corrupt militia to attempt a coup against Aristede. The coup was deemed unsuccessful after tens of thousands of Haitian citizens defended their new president in the streets of the capital city, Port-au-Prince. Eight months later, another coup was attempted, and this time Aristede resigned and exiled himself to Venezuela and the United States (Arthur).

At the end of 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristede became the country’s next president during the largest election in Haitian history. Aristede, a Catholic priest, won 67% of the vote by promising “justice, governmental accountability, and a chance for the population to participate in determining the nation’s future” (Arthur, 2007, p. 25). The result of the election prompted the former corrupt militia to attempt a coup against Aristede. The coup was deemed unsuccessful after tens of thousands of Haitian citizens defended their new president in the streets of the capital city, Port-au-Prince. Eight months later, another coup was attempted, and this time Aristede resigned and exiled himself to Venezuela and the United States (Arthur).

In 1994, the U.S. took action once again and sent 20,000 troops to help restore civil order. With the United Nations and World Bank’s help, an international financial package was put together and presented Haiti with $2.5 billion dollars in foreign aid. However, the benefits of this money were difficult to see on a macro-economic level. Without a prime minister, the country was unable to hold elections, so it remained without a leader for almost 2 years. Parliament member, Rene Preval, was appointed by the U.S. and temporarily became president by default. Shortly after the U.S. troops left in 1998, Aristede was allowed back into the country and was reelected president in 2000 with less than 10% of the population participating in the vote.

In 1994, the U.S. took action once again and sent 20,000 troops to help restore civil order. With the United Nations and World Bank’s help, an international financial package was put together and presented Haiti with $2.5 billion dollars in foreign aid. However, the benefits of this money were difficult to see on a macro-economic level. Without a prime minister, the country was unable to hold elections, so it remained without a leader for almost 2 years. Parliament member, Rene Preval, was appointed by the U.S. and temporarily became president by default. Shortly after the U.S. troops left in 1998, Aristede was allowed back into the country and was reelected president in 2000 with less than 10% of the population participating in the vote.

And finally, after a violent revolution, Aristede was once again forced out of office and fled the country to South Africa. During April of 2008, Aristede’s former prime minister, Rene Preval was elected by an 88% plurality of Haitian citizens (Arthur, 2007).

This 200 year account of Haiti’s cycle of revolution illustrates the Haitian people’s yearning for a stable and independent society; one free of corruption and patronage. Despite the injustice inflicted upon the Haitian people since the arrival of the first colonists, the desire for a better life has been ever present in the hearts and minds of these proud people. The underlying principal of their hope can be attributed to the Haitians’ deep belief in God, both Christian and Voodoo (Desrosiers & St. Fleurose, 2002). The extreme poverty in most areas of the country contrasts with the wealth of an intrinsic culture that Haitians exhibit in their artistic expression, religious faith, and strong work ethic.

This 200 year account of Haiti’s cycle of revolution illustrates the Haitian people’s yearning for a stable and independent society; one free of corruption and patronage. Despite the injustice inflicted upon the Haitian people since the arrival of the first colonists, the desire for a better life has been ever present in the hearts and minds of these proud people. The underlying principal of their hope can be attributed to the Haitians’ deep belief in God, both Christian and Voodoo (Desrosiers & St. Fleurose, 2002). The extreme poverty in most areas of the country contrasts with the wealth of an intrinsic culture that Haitians exhibit in their artistic expression, religious faith, and strong work ethic.

During her 2008 visit to HSC, Katie scraped paint off the main building in preparation for a new coat of paint.