By Tim Traynor, Director of HSC Facilities

By Tim Traynor, Director of HSC Facilities

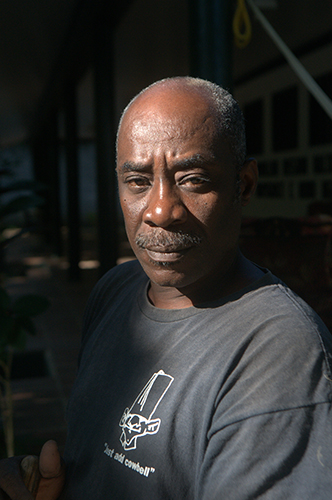

Every day, there is an older man who rakes the leaves at Hôpital Sacré Coeur, in the courtyard outside my small room at the compound where I spend nine months of the year. His name is Fan Fan. He rarely speaks. His head is bent down, staring at his endless task, like Sisyphus trudging up the hillside with his familiar burden. And like that mythical character, each morning the gods rain more leaves on the dusty earth as if to torment him as the sun mounts the sultry, Haitian sky.

I often wonder what he thinks about while scraping the little stones and packed earth that uphold my view. A man well into his fifties, Fan Fan’s arms flex in a pedestrian motion; blood and sweat course toward receptive muscles, while he labors under the heated and airless canopy. There is a quiet determination in his movements, urging each leaf and twig into careful piles, as though a wood stork was building its nest. There is no rush, no pending deadline; no need to impress for the potential is only another rendezvous tomorrow with Nature’s debris.

Fan Fan is an unusually lucky man. He has a rake and his leaves to provide sustenance for him and his family. But just beyond the crude concrete walls that surround the hospital, there are so many forgotten souls that will never have such opportunity; a blurring multitude of hungry need that spends the days wandering the landscape looking for food or work or some meager flint to strike the fire of opportunity, a means by which to survive.

I met Fan Fan’s daughter one day, a lovely woman of about twenty. She was bringing her father his lunch, a small clump of rice and a few slices of fried plantains. She bore a carriage of promise and moved about with confidence, a human work rooted in a hard bought education worn outside for all to see. Her father’s broad smile revealed that she was his treasure, an investment worthy of his labor.

I met Fan Fan’s daughter one day, a lovely woman of about twenty. She was bringing her father his lunch, a small clump of rice and a few slices of fried plantains. She bore a carriage of promise and moved about with confidence, a human work rooted in a hard bought education worn outside for all to see. Her father’s broad smile revealed that she was his treasure, an investment worthy of his labor.

I often think of that young woman as Hope, unblemished by the abject failure that permeates a country rife with disappointment. Those of us who work here, often see only that which is wrong and fail to see these bright glints of possibility, pathways to the future solutions and fervent resolve.

In my case and on occasion, I have performed a sort of compromise between my own failures to meaningfully alter events in this troubled land and the determination to feed success with the tools and skills to sustain it.

Poverty is a cruel partner to the human condition. It is a ghostlike horse born of apathy and misery that gallops alongside those too weak to escape its flaring nostrils and burgeoning hooves. It strikes down the fragile and deposits them at our doorstep where it is incumbent upon us to pick up these rejected spirit bundles and pull from them the humanity wrapped inside.

Fan Fan’s generation – and those who came before them, all the way back to 1804 – has struggled to survive in a country led by men of varying degrees of ability. You often hear that the old days were better. The roads were maintained and the telephones rang and were answered and people still had the dignity of work. Perhaps – indeed, almost certainly – they were romanticizing those times, but it is nonetheless an indication that there is a perception among some that the quality of their lives has declined.

Fan Fan’s generation – and those who came before them, all the way back to 1804 – has struggled to survive in a country led by men of varying degrees of ability. You often hear that the old days were better. The roads were maintained and the telephones rang and were answered and people still had the dignity of work. Perhaps – indeed, almost certainly – they were romanticizing those times, but it is nonetheless an indication that there is a perception among some that the quality of their lives has declined.

I have witnessed countless groups of nervous teenagers and their chaperones hanging about Touissaint Louverture Airport in Port au Prince, clad in themed T-shirts that declare their intentions to save a little piece of world, awaiting their adventure into this exotic place. They are filled with anticipation and some trepidation over what promises to be a unique and perhaps life altering experience.

And then there is another group of volunteers, not so animated, sitting quietly, almost reverential that has just had their encounter with poverty, up close and very personal. They are now eyewitnesses to a tragedy that continues to unfold. They now know that there are no easy fixes. They know that the problems are enormous and complicated.

Maybe they noticed his will to endure and maybe not. But hopefully each of them, each of us, can recommit, re-steel ourselves, to the idea that despite all of the leaves that fall upon the ground, the Haitians will persevere in their quest to create a society that can feed itself, benefit from good healthcare and a modern education, and build a culture that promotes something other than survival.

Tim Traynor is Director of Facilities at HSC. A Master Electrician and former owner of a large New England based contractor and real estate development firm, Tim has worked in Milot for over 6 years and splits his time between Haiti and his home in Kiawah Island, South Carolina.

Tim Traynor is Director of Facilities at HSC. A Master Electrician and former owner of a large New England based contractor and real estate development firm, Tim has worked in Milot for over 6 years and splits his time between Haiti and his home in Kiawah Island, South Carolina.